An Indian will land on Moon’s surface in 2040: Jitendra Singh

Dr Jitendra Singh highlighted the historic landing of Chandrayaan-3 on the Moon's South Pole, a feat that astonished the world and established India as a leader in space exploration.

Our mobile phones pack more punch today than the computer on board Apollo 11, 50 years ago. So how did we make the Moon landing in 1969?

PHOTO: GETTY

Many people who are old enough to have experienced the first moon landing will vividly remember what it was like watching Neil Armstrong utter his famous quote, “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” Half a century later, the event is still one of the top achievements of humankind. Despite the rapid technological advances since then, astronauts haven’t actually been back to the moon since 1972.

This seems surprising. After all, when we reflect on this historic event, it is often said that we now have more computing power in our pocket than the computer aboard Apollo 11 did. But is that true? And, if so, how much more powerful are our phones?

On board Apollo 11 was a computer called the Apollo Guidance Computer. It had 2048 words of memory, which could be used to store “temporary results” — data that is lost when there is no power. This type of memory is referred to as Random Access Memory. Each word comprised 16 binary digits (bits), with a bit being a zero or a one. This means that the Apollo computer had 32,768 bits of RAM memory. In addition, it had 72KB of Read Only Memory, which is equivalent to 589,824 bits. This memory is programmed and cannot be changed once it is finalised. A single alphabetical character — say an “a” or a “b” — typically requires eight bits to be stored. That means the Apollo 11 computer would not be able to store this article in its 32,768 bits of RAM. Compare that to your mobile phone or an MP3 player and you can appreciate that they are able to store much more, often containing thousands of emails, songs and photographs.

Advertisement

Phone memory and processing

To put that into more concrete terms, the latest phones typically have 4GB of RAM. That is 34,359,738,368 bits. This is more than one million (1,048,576 to be exact) times more memory than the Apollo computer had in RAM. The iPhone also has up to 512GB of ROM memory. That is 4,398,046,511,104 bits, which is more seven million times more than that of the guidance computer.

But memory isn’t the only thing that matters. The Apollo 11 computer had a processor — an electronic circuit that performs operations on external data sources — which ran at 0.043 MHz. The latest iPhone’s processor is estimated to run at about 2490 MHz. Apple do not advertise the processing speed, but others have calculated it. This means that the iPhone in your pocket has over 100,000 times the processing power of the computer that landed man on the moon 50 years ago. The situation is even more stark when you consider that there will be other processing built into the iPhone, which looks after particular tasks, such as the display.

What about a calculator?

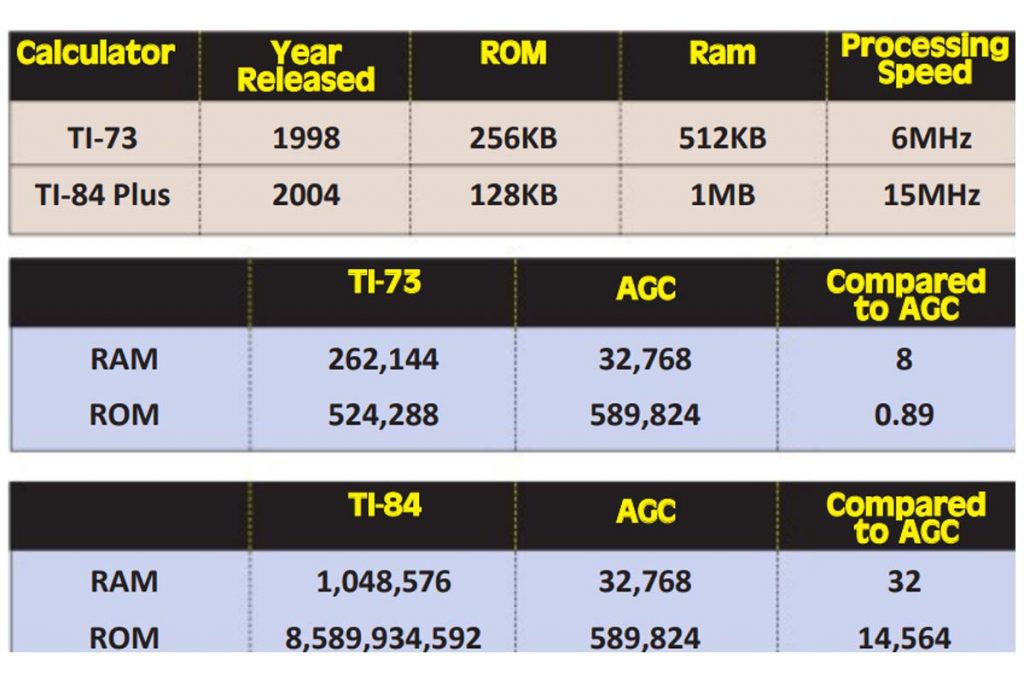

It’s one thing comparing against a state-of-the-art phone, but how did the Apollo 11 computer compare against a classic calculator? Texas Instruments was one of the most famous manufacturers of calculators. In 1998, they released the TI-73, and in 2004, they released the TI-84.

The tables (above right) show the specification of these two calculators. If we compare the two calculators against the Apollo guidance computer we can note that the TI-73 has slightly less ROM, but eight times more RAM. By the time the TI-84 was released, amount of RAM had increased to 32 times more than the Apollo computer and the ROM was now more than 14,500 times more. With regard to processing speed, the TI-73 was 140 times faster than the Apollo computer and the TI-84 was almost 350 times faster! It’s mind-blowing to think about that a simple calculator, designed to help students decades ago pass their exams, was more powerful than the computer that landed man on the moon.

What if Apollo 11 had had a modern computer?

The Apollo computer was stateof-the-art in its time, but what would have been different if the moon landing had the state-of-the-art computers that are available today? I suspect that the software development time would have been a lot faster, due to the software development tools that are available today. It would have been a lot quicker to write, debug and test the complex code required to deliver a man to the moon.

The user interface called Display Keyboard had a calculator-type interface where commands had to be input using numerical codes. Today’s interface would be a lot easier to use – – which could matter in a stressful situation. It would almost certainly not have a keyboard, but would use swipe commands on a touch screen. If that were not possible, due to having to wear gloves, the interface might be through gestures, eye movement or some other intuitive interface. Surprisingly, one thing that wouldn’t be better today is the communication speed with Earth. The actual time it takes to communicate is the same today as it was in 1969 — that is, the speed of light, which means that it takes 1.26 seconds for a message to get from the moon to Earth. But with the larger files we now send — and from greater and greater distances — to get an image from a spacecraft to Earth today will take relatively longer than it did in 1969. That said, it would look much prettier thanks to advances in camera technology

Perhaps the biggest change we would see is the computer being a lot more artificially intelligent. I am sure that the flying and landing of the space craft would not be put solely into the hands of the computer, but it would have much more information and intelligence, and would be able to make many more decisions than the Apollo 11 computer was able to do in 1969. This could be a huge relief for the astronauts. Armstrong did say that, on a worrying scale from one to ten, walking on the moon was about a one — whereas making the final descent to land was about a 13.

So let us end by acknowledging what it took to land people on the moon in 1969 with the limited computing power that was available at the time. It really was a remarkable achievement.

The writer is professor of computer science, University of Nottingham, UK.

Advertisement